Living Memory, Living Traditions: Visions of a Lasting Nubia

July 7 Marks International Nubia Day!

The Nubian civilization, rooted along the Nile’s southern regions in what is today northern Sudan and southern Egypt, holds a unique place in world history. July 7 marks International Nubia Day, and the Black Writers and Journalists’ Workshop is publishing the project called “Living Memory, Living Traditions: Visions of a Lasting Nubia,” which amplifies the stories of Nubian writers, advocates and allies who are working to resurface ancient and modern Nubian history, preserve cultural traditions, and revive indigenous languages.

This article is a collaborative feature that represents the work of four Nubian writers, stewarded by project editor Aurora Ellis and project coordinator Ola A.

“Nubia, is believed to derive from the ancient term “Nub”, meaning gold, a reference to the region’s historic abundance of this precious resource,” said Bakri Gamal Khairi, who says Nubia’s legacy, extends far beyond material wealth, encompassing a profound cultural and linguistic heritage that has survived for millennia and now draws visitors from across the world.

And while Nubia’s history is little taught, Nubian communities retain their connections to ancient Nile Valley civilizations. In recent years, international campaigns of awareness have captured the imagination of tourists, scholars, and researchers from around the world, especially those interested in unearthing Africa’s pre-colonial past.

“It is vitally important that the world continue to be informed about Nubia. The Nubian civilization is an ancient and important one in Africa,” says Annie Jennings, an anthropologist who lived and studied in villages in Aswan, Egypt, during the 1990s.

“Many people, mainly scholars, know that Nubia arose during prehistoric times, and became wealthy and powerful as the Kingdom of Kush (2,500 B.C. – A.D. 300),” she said. “The Kushites invaded ancient Egypt and ruled as the 25th Dynasty for approximately 100 years. Even after this, ancient Kush continued to thrive for another 1,000 years in the area between the 5th and 6th Cataracts.”

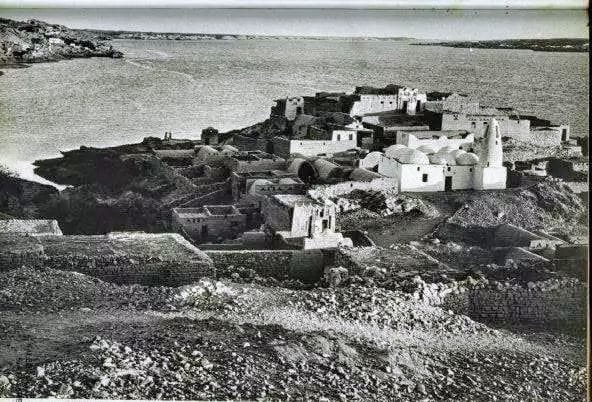

Efforts to preserve and uncover history come after many Nubian communities faced decades of displacement and marginalization following the construction of the Aswan and Merowe dams in Egypt and Sudan, respectively. Designed to expand the country’s agricultural production of cotton and boost economic exports, the dams also forcibly removed communities who made their way of life by the Nile.

“If you ask a Nubian or an Egyptian about the forced displacement of the Nubians, many would believe it happened only once in 1964, with the first village to be displaced being Daboud. However, the truth is that the Nubian displacements occurred multiple times over different periods,” says Nubian cultural advocate Ondy Soliman, who detailed that between 1898 – 1964 year there were at least seven displacements that led to a large Nubian diaspora outside of their ancestral homelands.

Each time Nubians were the scattered either throughout neglected settlements surrounding Aswan, or they moved further across Egypt and abroad to the Gulf countries, Europe, the United States, Jordan, Chad, and Sudan, he said.

But being forced to leave your homeland in search work and to escape poverty is another kind of displacement too, he adds. And with this series of displacements, memories and traditions – passed down from elders whose experiences were rooted in their presence on the land for over a millennium – are now at risk.

Language links back to land and history

Cultural advocates today aim to inspire the youth to learn the Nubian language. They say it’s an opportunity to not just promote the language, but also to teach about its linkages to various civilizations and cultures in the region throughout the centuries.

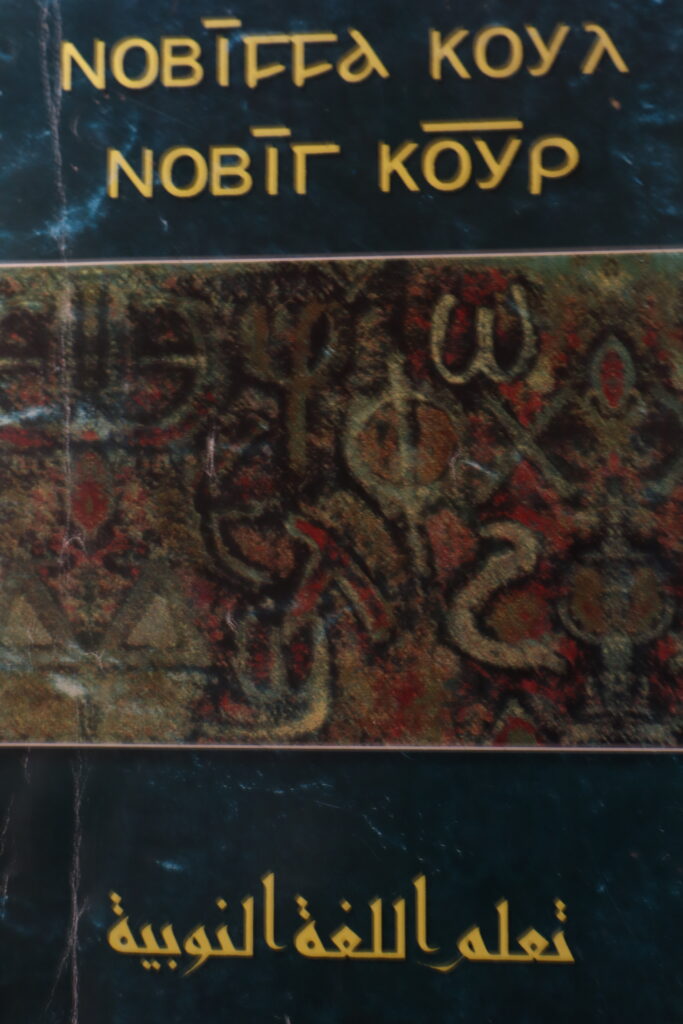

“The Nubian language, classified as a Nilo-Saharan language,” writes Gamal Khairi, who hails from Nasr Nuba and works in the field of tourism sharing his knowledge of history with visitors. “Nubian has largely persisted as an oral tradition, even as its speakers adopted various writing systems throughout their history — from ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics, to Demotic, Coptic, and Ancient Greek scripts.”

Nubian communities – like most in Sudan and Egypt – are Muslim, but they have a diverse religious history that includes during the period of Medieval Nubia, which was a Christian kingdom.

Gamal Khairi said that as early as the sixth century Common Era, Nubian language was adopted by local churches for liturgical use, with parts of the Bible translated into Nubian.

Modern Nubian is categorized into two principal branches – Nobin spoken by the Fadija, Mahas, Halfa, and Sikoot groups in the southern regions of Nubia across both Sudan and Egypt and Oushkreen (also called Dongolawi and Kenuzi), spoken primarily by the Dongolawi in Sudan and the Kenuz in southern Egypt.

He also notes the language reflects a deeply rooted connection between the language, land and experiences with the environment.

“For instance, the word for thunder (Dow dowe) echoes the actual sound of thunderclaps; the term for lightning (Aroon fele) describes its resemblance to the burst of brightness from an emptied palm date cluster.”

As certain elements of Nubian daily life vanish, so too do the words that described them with such precision, he said.

To ensure the survival of the Nubian language, several strategies have emerged within the community, including informal educational initiatives that have begun to incorporate Nubian vocabulary into children’s daily lives, he explained.

Modern technologies, including smartphone apps and online social platforms, are now being employed to document and teach the language to new generations.

Music as a living tradition

Nubians sing throughout all aspects of daily life—while working, resting, on the waterwheel, aboard the boat, during play, and in moments of both seriousness and joy, says Nubian researcher Fathy Gayer, who comes from a family of prominent singers, poets and musicians.

“Singing is deeply woven into the cultural fabric of Nubian life, expressing love, reverence for nature, happiness, sorrow, and lament,” he said. “The melodies and rhythms are drawn directly from the surrounding environment: the sound of waterwheels, the rustling of palm fronds in the breeze, and the calls of birds.

The rhythm or tempo varies depending on the environment and the nature of the task being performed. It is heavily influenced by the pentatonic scale, which serves as a fundamental structure in much of Nubian musical tradition, Gayer added.

“For example, a farmer tilling the soil with his hoe synchronizes the striking of the hoe and the movement of his feet to create a rhythmic accompaniment to his singing. The person operating the waterwheel matches his melody to the gentle, continuous sounds of the continuous sounds of the turning wheel.”

One of Nubia’s most famous musicians is Hamza Alaa el-Din, who sung ballads with his oud, summoning the image of the water wheel.

Gayer also notes the important place of Nubian women in traditional music as well.

“Mothers soothe their infants with gentle lullabies, singing melodies that help the child drift to sleep,” Gayer added, describing scenes that are familiar to many who visit Aswan. “In moments of mourning, women employ deeply sorrowful musical modes that reflect the gravity of the occasion, reciting the virtues of the deceased in a manner that evokes profound emotion.”

Gayer reminds us that for Nubians, the song is not just entertainment; it remains a living tradition among the people.

Memories of Communal Solidarity

“Life in Drowned Nubia was greatly supported by the communal lifestyle,” says Yahya Saber, a Nubian elder who remembers life before in Old Nubia in the 1950s and 1960s before the mass displacement by the construction of the Aswan Dam.

“Almost all the people in the village were relatives belonging to one tribe, and the closest relatives lived on the same street, even in the same small neighborhood (Nagaa). Therefore, no one would enjoy their food without their neighbor. We and the neighbors always ate together.”

Narratives from elders of close-knit communities and big families that at depended on one another and shared with each other are common.

“The nature of life there helped to strengthen solidarity,” Saber said, adding “since society there was far from artificial urban life — except for the post and telegraph. There was no electricity, no paved roads, no cars, and thus no devices.”

“I remember that my family (my father, mother, and sisters) lived in Cairo, and they used to send me packages containing everything, especially things that were not available in Drowned Nubia. My grandmother used to distribute the contents of the package to the neighbors, who were our relatives, and keep a small portion for us. Our neighbors would do the same when they received packages from Cairo or Alexandria.”

The lessons of communal life though, extended beyond just sharing with family and was an important element of wider community belonging and support.

“I remember that my grandfather, may God have mercy on him, never turned anyone away from his shop, whether they had money or not,” Saber said, adding that bartering was another common method of sharing.

“Our life was based on love, cooperation, and complete solidarity.”

Exploring History, Culture Creates New Forms of Kinship

Tim and Ingrid Briscoe, American tour guides who live in Alexandria, Egypt, have been going to Aswan for years to lead groups of tourists from Europe, North America and South Africa, saying visitors recall their time in Aswan as cherished memories. “We have seen them fall in love with the Nubian culture and people,” they said.

For Wakeya Smith, a Black American who visited Aswan and described her time there as a journey of kinship.

“My family roots stretch back generations in the United States, primarily in the Deep South. I was raised among more than 60 grandchildren, in a family where love was loud, where at family reunions we would eat, dance, encourage our youth, honor our elders, and pay respects for our family who are no longer with us and share family stories,” she said.

“When I traveled to Egypt, including to Aswan to visit the Nubian Village, I did not expect to feel something so familiar in a place I had never been. But that’s exactly what happened. … The warmth hit me instantly—not just the sun, but the people from the moment we arrived.”

She added: “What surprised me most was how many Nubians I met who knew of the Black American experience in the U.S and wanted to know more. We talked openly. about our histories and experiences. We share our ability to hold fast to our history and identity, even while there are efforts that try to erase it. At times, I saw myself reflected in them and them in me.”

International Nubia Day puts the spotlight on Nubia culture, but it is also used to promote continued archeological and historical research, which not only draws visitors and tourists from around the world but uncovers neglected knowledge about one of Africa’s oldest civilizations.

“We should preserve everything that is being dug up by archaeologists in Sudan that will tell us more about how the ancient Nubians lived. The sites of Kerma, Napata, and Meroe are especially important for this,” said Jennings.

“So much of this history has been hidden from us, but Nubians are proud of their heritage and customs because they are aware that this history is true.”

The Black Writers and Journalists’ Workshop is a small volunteer-run, donation-based project designed to train and support emerging authors and editors. Our mission is to educate and inform Black audiences, the general public and policymakers, publishing vibrant, deeply reported stories reflecting the everyday lives and realities of African Americans and Black diaspora communities.